Traditional Chinese notation - the emphasis of the process rather than the result

In Western music, we cannot hear the music by the ancient Greeks since they did not have a system to notate the music before Guido of Arezzo, the development of staff notation in the 10th century.

This also applies to Chinese music. This is an example of the oldest notation of Chinese music in the 7th century. It is a score for guqin (Chinese zither). The notation is text-based (wenzipu), telling the performer the playing position (relative pitch) and the playing technique word by word. However, there is no accurate tempo, rhythm, articulation, or tuning. The situation resembles the western staffless neumes. We have the direction but don't know where to start. Listen to the free-flowing rhythm of the example

The performance of the score below

|

| Text-based notation of Jieshi Diao Youlan |

The text-based notation is complex, people simplify the notation to tablature (Jianzipu) for guqin in the 10th century. But the problem of lack of rhythm still was not addressed.

The main beat is reinforced by percussion. It is full of rubato and the ensemble closely follows the singer, not in exact timing. The slight apart helps to demonstrate the tone color of the instruments. (My precious article also wrote about tone color and the heterophonic texture) That is quite different from western practice, when I learned to play a flute piece, my teacher always asked me to use a metronome and count the subdivision.

Like the lead-sheet in jazz music, the less-is-more design of Chinese notation allows room for artists to improvise. The ensemble plays the same melody in heterophony, individual players improvise (jiahua) or simplify the original melody (qupai). The authorship of the original melody is not important nor the role of the composer (Chou, 2007). The role of a performer also served as a composer. Each performance is the process of creating rather than the faithful representation of the previous result. In the genre of guqin music and yayue (court music), the performing or listening of the music served a process of cultivation, becoming a better person that traditional Chinese philosophers believed. (The earliest Mozart Effect?) The simplicity can keep the listener from distraction.

|

| Tablature of guqin |

We can see that guqin has a very special position in Chinese music, having a dedicated notation for it. Intellectuals had to study it as basic cultivation. For more info, please read Chou's (2007) thesis.

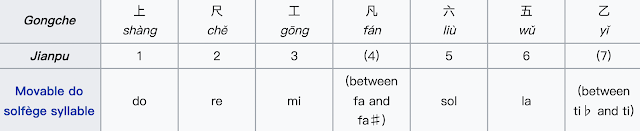

In Chinese folk tradition, the notation for other instruments and songs, gongchepu developed in the 9th century is the first choice. The notation of Chinese music had not been developed for a long period of time until Western notation surged the nation. For the pitch in this notation, it uses solfege and movable "do" system, there is no absolute pitch for starting with. For most scenarios, there is only one single melody in the score.

|

| Corresponds to Gongche and solfege |

The notation is not accurate in terms of rhythm. It provides a musical skeleton. The details are usually passed on by oral tradition. "。" or "x" denotes the stronger beat, called ban and "、" denotes the weaker beat, called yan. In other words, the notation only shows the main beat, the rhythm of the notes in between the main beat can be freely interpreted. However, players should avoid playing the rhythm in a strict subdivision (Chen, 2020). (Wiki does not mention that).

Cantonese opera in gongche notation

Like the lead-sheet in jazz music, the less-is-more design of Chinese notation allows room for artists to improvise. The ensemble plays the same melody in heterophony, individual players improvise (jiahua) or simplify the original melody (qupai). The authorship of the original melody is not important nor the role of the composer (Chou, 2007). The role of a performer also served as a composer. Each performance is the process of creating rather than the faithful representation of the previous result. In the genre of guqin music and yayue (court music), the performing or listening of the music served a process of cultivation, becoming a better person that traditional Chinese philosophers believed. (The earliest Mozart Effect?) The simplicity can keep the listener from distraction.

References:

Chen, S. R. (2020) Cantonese opera learning and singing: Wang Yuesheng's syllabus in Cantonese opera. Shangwu, Hong Kong. ISBN:9789620758409

Chou, W. (2007) Whither Chinese composers? Contemporary music review. [Online] 26 (5-6), 501–510.

Xiangpeng, H. (1992) Ancient Tunes Hidden in Modern Gongche Notation. Yearbook for traditional music. [Online] 248–13.

Comments

Post a Comment